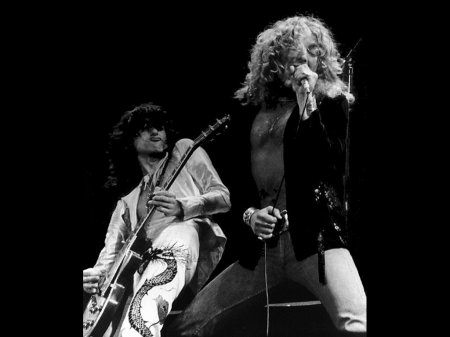

The photos are timeless: A young Miles Davis shrouded in smoke, eyes closed in concentration and silver trumpet clasped like a weapon; Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant caught in mid-howl, blonde mane flying, as guitarist Jimmy Page rips out a power chord behind him; the Rolling Stones at the pinnacle of their early 1970s musical potency, Mick and Keith prowling the stage like young gods.

These and hundred of other iconic images have come to define the look, the feel and perception of entire eras of music, augmenting legends and enshrining for the ages pivotal moments in the careers of the most influential musicians in the world.

Sadly, the access required to take these kinds of photos is becoming increasingly rare in today’s music world. In fact, under photography guidelines currently adhered to by many artists and venues, they have become all but impossible to capture.

As a music fan and a professional photographer who routinely attends concerts, I find the current trend of allowing photos during only the first three songs of an artist’s set to be both ungracious and counterproductive to quality work.

That kind of constricted working environment would have been laughable to the great concert photographers of the past, many of whom were nearly as well known as the rock, pop, blues and soul music stars they covered.

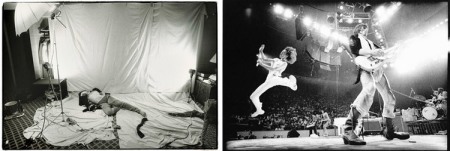

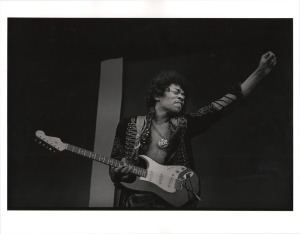

In the 1960s, Jim Marshall captured timeless shots of Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix at the Monterey Pop Festival and Woodstock. The ’70s saw the rise of celebrity music photographers such as Annie Leibovitz, Mick Rock, and Bob Gruen, visual artists who captured everything from the Rolling Stones’ backstage debauchery to the up and coming New York punk scene featuring bands such as The Ramones, Blondie, and The Talking Heads.

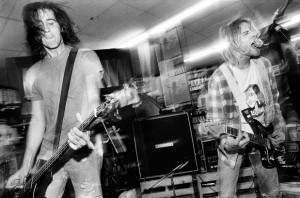

More recently, in the early ’90s the work of Charles Peterson helped spread the word about the emerging Seattle music scene through early images of Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains and others.

The work of these photographers simply would not have been possible under the current restrictions. The objections to limiting photographs to the first three songs of a set are too numerous to list here, so I’ll just discuss several that come immediately to mind:

• The best photo opportunities rarely come during the first three songs. Like car engines and athletes, bands need time to warm up. They generally spend the opening numbers of a set getting a feel for the audience and the venue. Rare is the band that hits the stage at full throttle or gets there in their first 15 minutes on stage.

• The three-song rule applies only to professional photographers with professional equipment. Anyone with a cell phone can continue to snap off blurry, low-resolution pictures or even record videos while blocking the view of those standing behind them. It’s a surreal experience to have a security guard admonish you for crouching at the lip of the stage with your $1,200 Nikon and $300 lens while, inches away, dozens of cell phone cameras click away.

• It treats photographers not as working professionals but as annoyances to be dealt with as quickly as possible and then gotten out of the way.

Personally, the part of these restrictions that angers me the most is that they completely ignore the mutually beneficial relationship that once existed between photographers and musicians. The fact is, music makers have always relied on images to keep their names in the press, and those classic photos I mentioned at the beginning of this column did as much to cement those artists’ reputations as anything they put on record.

All of this strikes me as just another symptom of artists attempting to control every aspect of their image, to let nothing go out into the world that hasn’t been thoroughly vetted and sanitized. It’s a mindset that makes for the kind of bland, aggressively inoffensive articles and photos found in magazines like Rolling Stone, which recently decided to airbrush away certain protruding parts of the female anatomy in photos included as part of a feature on one of the biggest pop performers in the world.

As a remedy to this ridiculousness I’d like to make one very simple request of venue managers, concert security, and most of all, the artists on stage: Do your job as a professional and let us photographers, as annoying as we may be, do ours.